Saving money: Virtue or vice? A fascinating exhibition explores Germany’s favourite national occupation in its historical and current context…

(c) Historisches Archiv der Erzgebirgssparkasse Schwarzenberg, Thomas Bruns DHM

The idea of diversifying one’s financial portfolio dates back to at least the fourth century AD, when Rabbi Issac bar Aha documented a rule for asset allocation in the Babylonian Talmud (Tractate Baba Mezi’a, folio 42a): “One should always divide his wealth into three parts: a third in land, a third in merchandise, and a third ready to hand.” Building lasting wealth starts with saving. However, Jewish wealth is a popular stereotype, and to ward off this bias, scholars attribute Jewish success in business to Jewish culture, which emphasizes literacy and education as much as it values charity. German thriftiness is another unchecked generalization. While the German habit of saving money has come to define the national character, it also serves as point of international criticism toward Germany during the eurozone crisis.

In one of its current shows, the German Historical Museum in Berlin, in cooperation with Berliner Sparkasse, takes a look not only at the financial but at the cultural roots of German saving. “In the discussion about the financial crisis, Germany, as the representative of a strict austerity policy, is severely criticized in many European countries,” says Raphael Gross, the museum’s director. “These attacks are met with little understanding in Germany. Why is this conflict so highly emotionally charged? The historical dimension could play a role in answering this question.”

Saving has a long history in German society. The first savings bank opened in 1778 in Hamburg. By 1836, there were more than 300 of these savings banks operating in the then-German Confederation, allowing Germans to save their hard-earned income for some interest.

The exhibition puts this development in a European context. Some elements of institutionalized saving, like financial institutions providing poor relief or personal funds for bad times, existed long before the first savings bank was set up. Members of the Franciscan order established loan funds called Monti di Pietà (Mount of Piety) in many Italian cities in the 15th century. Serving as institutional pawnbrokers, they gave low-interest credit to the needy in hard times. The aim of these funds was mainly to challenge Jewish moneylenders and to oust them from this branch of business. After loan funds were established in a city, the Jewish population was often expelled. The first-ever proposal for a savings fund was made by French financial official Hugues Delestre in 1611 at the beginning of the mercantile era.

(c) Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin

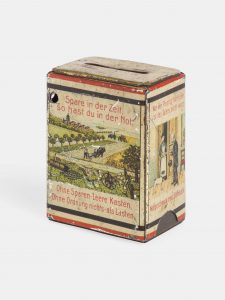

When the first savings institutions were founded in Germany, they helped educate people to be hardworking and thrifty. The individual was supposed to benefit the community. There is also a Protestant tradition of saving and restraint. When the workers’ movement gained strength, its political opponents also recognized the importance of austerity for perpetuating existing conditions and exploited this. Their argument was that people with savings to lose were less open to revolutionary ideas. Thrift was also taught in schools. The motto of a home money box from 1900 displayed in the exhibition reads: “Without order, nothing but loads.”

Anti-Semitic stereotypes

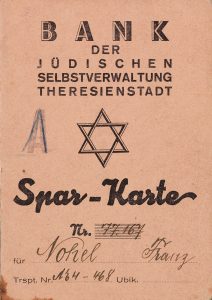

From the founding of the German Empire in 1871, anti-Semitic stereotypes were increasingly counterposed to the idealized image of industrious, thrifty Germans. During the Weimar Republic, virtuous saving, based on creative work, was distinguished from the “money-grubbing” of Jewish capital, believed to have played a role in the hyperinflation of 1923. This thinking later became a core element of Nazi ideology. There are examples of anti-Semitic propaganda in the exhibition, but one item is even more disturbing. It is a savings card of Franz Nohel, issued by the Jewish self-administration in Theresienstadt in March 1945. The savings plan was part of a program of deception prepared by the German authorities in the Ghetto.

After World War II, the savings of German individuals depreciated seriously due to currency reforms in both parts of divided Germany. Nonetheless, this did not prevent them from quickly starting to save substantial amounts again. Thrift and its associated moral concepts were still promoted as beneficial. Through today, saving has remained firmly entrenched in Germany, a society that takes pride in the solidity of its public finances and in its balanced budgets. “Saving is seen as the morally right thing to do,” says Kai Uwe Peter, the managing director of Berliner Sparkasse, a savings bank that boasts some two million clients in the capital. “It is more than a simple financial strategy.”■

Saving – History of a German Virtue is currently on display at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin and runs through August 26, 2018