It’s high time for restitution procedures to be stepped up in order to ensure that art works are returned to their lawful owners, says Karin Prien…

Karin Prien

(c) JVG

The National Socialist tyranny becomes increasingly a part of the past for most people in Germany. In everyday life, at home, there are fewer and fewer traces of that particular time of our history. However, the victims and their families feel quite different. Many victims – and I count among them those who are affected in the second, third or even fourth generation – still have the proverbial blank spot on the wall or an empty spot on the shelf. A painting belongs in this blank spot. A picture with meaning, a picture with history. A work of art, which once belonged to the family, maybe with great economic and non-material value. The arts do form our society. This applies not only to the big picture, but also to the small one. The painting on the wall that tells the story of the family. The statue, which was the most valuable treasure of the family. The Nazis robbed the Jews of their cultural assets and enriched themselves with them. More than 70 years after the Nazis were defeated, families and their relatives are still struggling to reduce these injustices.

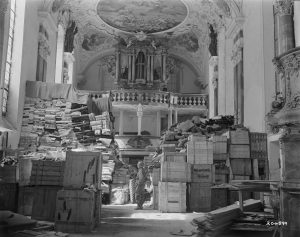

US soldier surveying looted art in a church in Ellingen, 1945

(c) Public Domain

The return, the so-called restitution of works of art, is rarely easy to achieve. Too often the origin of artworks is not completely clarified. Too often the descendants of the former owners of the artworks must first establish their ownership. In spite of the growing importance of art works and the continuing development of provenance research, it is often not easy to clarify ownership. It is a matter of legal, procedural and moral-ethical questions. In order to facilitate these procedures, the Limbach Commission has existed in Germany since 2003. The Limbach Commission is formally called the “Advisory Commission in connection with the return of National Socialism persecution-related confiscated cultural assets, especially from Jewish property” and is named after its first chairwoman, the now deceased President of the Federal Constitutional Court, Ms. Jutta Limbach. Its mission is to mediate in disputes between museums and descendants of the original owners of works of art and to bring about a fair solution.

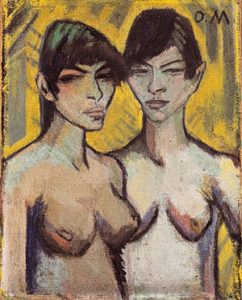

(c) Public Domain

Only 15 cases solved

But the very name “advisory commission” gives an indication of where the limits of this commission lie. The Limbach Commission is only binding in its decision if both parties have agreed to this binding effect in advance. There is thus no binding legal basis for the commission’s work. Nor can a commission decision be legally enforced. An additional problem is that in the event of a dispute, both parties must appeal to the commission. It is not possible for just the descendants to call on the commission to reach an amicable settlement in a dispute over a stolen work of art. On the commission’s website you can read that since its first meeting in 2003, the commission has only decided 15 cases. This is partly because the commission’s members are volunteers: High-ranking personalities from politics and society who have many other commitments. At the same time, the commission has few resources and no staff of its own to investigate the history of a work of art.

With the Washington Principles of 1998, 44 states, including Germany, committed themselves to identifying artworks confiscated during the National Socialist era, locating their pre-war owners or heirs, and finding a just and fair solution. This is easier said than done. There are good reasons why the arts and cultural heritage in Germany fall under the sovereignty of the states.

The overwhelming majority of museums in Germany are supported by the states and municipalities or by private associations and foundations. There is no universal Restitution Act in Germany, such as the one in Austria. It is therefore one of the most important tasks of the newly created Conference of Ministers of Culture to find a solution to this problem. At the first meeting, which took place this March, we therefore decided to take up this problem again with the aim of finding a uniform regulation that would deliver binding results within a reasonable time. Achieving legal certainty and a clarification of ownership in a transparent procedure based on clear legal bases is not only important for heirs. It is also in the interest of the museums in our country. The same is true for artworks from the colonial period. Many pieces from this time, which were stolen from people, violating their culture, their faith and their privacy, do still exist in our museums.

It is a problem that we must address. The blank spot on the wall, this gap that shows many families where the National Socialists robbed and disenfranchised their parents and grandparents, must not remain empty. As a state under the rule of law, but also as a nation that highly values culture and the arts, we must ensure that we achieve efficient and fair restitution procedures.■

Karin Prien (CDU) is Minister for Education in the state of

Schleswig-Holstein