“Our desire for culture equalled our desire for life…” Music helped preserve humanity under inhuman conditions in ghettos and concentration camps…

Under the conditions of extreme brutal oppression, especially under National Socialism and Stalinism, with the ultimate goal of the destruction of human life, active resistance of the victims was only possible in exceptional cases. Disengaged, isolated, and robbed of elementary living conditions, men and women could express their resistance, if at all, only through their spirit. This included above all the preservation of humanity despite inhuman conditions. Although the struggle for physical survival under these circumstances should have absorbed all their energy, many of them still found the energy for spiritual activity, which in turn provided essential moral support to their resilience.

Although research about music under the conditions of dictatorship has been a part of German musicological discourse since the 1960s, the first fundamental works in this area by Joseph Wulf and Fred K. Prieberg were hardly noticed. After Germany’s reunification, the topic was given new impetus. In particular, the history of the Theresienstadt ghetto, its rich cultural life, which was partly abused by the Nazis for propaganda purposes, and the works of the composers imprisoned in Theresienstadt attracted the attention of the general public. Over the past 25 years, a number of scientific publications and artistic projects, editions, television and radio productions, exhibitions and documentaries have been devoted to music from Terezin.

One initiative among others was the student run research group Exile Music at the Institute of Musicology at Hamburg University, which existed between 1985 and 2005, devoting itself to exploring German and Austrian Jewish musicians driven into exile by Nazi persecution. In addition to a book, publications and exhibitions, this workgroup now focuses on its online project Encyclopedia of Persecuted Musicians of the Nazi Era (Lexikon verfolgter Musiker und Musikerinnen der NS-Zeit).

One of the most important sources for music practice in concentration camps is the archive collection of Aleksander Kulisiewicz (1918-1982), which is shared between the memorial and museum Sachsenhausen and the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and has so far hardly been explored. Kulisiewicz was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp from 1940 to 1945. His archive contains over 700 pages of the unpublished manuscript in Polish on Music and Singing in Fascist Concentration Camps from 1933 to 1945 as well as more than 100,000 other documents and manuscripts on the subject.

Self-assertion

Hardly explored is the musical life in the Jewish Cultural Associations [Jüdische Kulturbünde] – a kind of Jewish cultural ghetto within Nazi Germany. Founded in 1933 as a self-help organization to support Jewish artists who had lost their jobs due to the occupational ban pronounced by the government, these Jewish Cultural Associations were tolerated until 1941. Although music events organized by local Cultural Associations in some major cities such as Berlin, Frankfurt, Dresden or Hamburg are partially documented, there is still very little known about the musicians who actually shaped Jewish musical life at the time, especially in the provincial cities. Even less attention has been given to compositions created under the conditions of Nazi rule and promoted by the Jewish Cultural Associations. But the creative activity of German-Jewish composers in the 1930s, despite their persecution, was extremely rich and pro-active. Among other things a composition competition, carried out in 1936 by the Reichs Federation of Jewish Cultural Associations (Reichsverband der Jüdischen Kulturbünde), is proof of that creativity.

One year after the Nuremberg racial laws were passed, when anti-Semitic measures were increasing, it was a daring undertaking to appeal to the creativity of Jewish composers. Quite unexpectedly, a total of 122 works were submitted. Apart from their quality, all these compositions were – more than anything else – testimony to the spiritual strength and cultural creativity of their creators. The first prize was awarded to Richard Fuchs from Karlsruhe for his oratorio Vom jüdischen Schicksal (About the Jewish Fate).

It was fully prepared for its premiere in 1937, which, however, had to be canceled at the last moment due to prohibition by Nazi authorities. To this day, the composition has not been performed. The manuscript lies in an archive in New Zealand.

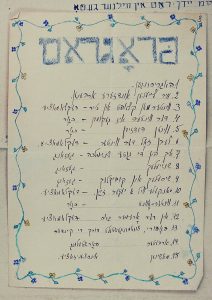

An important chapter in the history of the spiritual resistance in the Jewish ghettos established by the Nazis in Eastern Europe is the rich cultural life celebrated and nourished within. It has yet to be systematically researched and documented, although it is known that in the ghettos in Warsaw, Lodz, Lublin, Vilna, Kaunas, among others, concerts and other musical activities took place in the first months of their existence – and beyond. Also life in the concentration camps was not silent. There was music.

Until recently, musicology has also completely ignored the topic Music in the Gulag. But in 2014, the young musicologist Inna Klause published her doctoral thesis The Sound of the Gulag, which is a meritorious entry into promising research in this particular field. During the decades of Stalinism, musical activities took place in many Soviet camps. In addition to the prescribed music, there were also independent artistic activities, which helped to preserve the courage and human integrity of the prisoners. It would be an important task to continue and deepen this research.

Among the prisoners of the gulag were world-class musicians, such as Vsevolod Zaderatsky (1891–1953), who composed a cycle of 24 preludes and fugues for piano in a camp on the Kolyma River in north-eastern Siberia between 1937 and 1938. Zaderatsky was exposed to political persecution throughout his entire life in the Soviet Union; his music was outlawed by a total ban of performance. One CD anthology with piano works by Zaderatsky recorded by the author of this article, among them also the cycle of preludes and fugues, will be released in the summer of 2017.

The manifold traces of this spiritual resistance, which have largely disappeared in the past decades, are not only of aesthetic importance. They are also a testament to humanity and the European humanistic values that have been maintained in the decades of barbarism. The musical creativity under the conditions of the dictatorships can help current and future generations in search of their own cultural roots and their spiritual location, thus strengthening the foundations of our democracies.

Jascha Nemtsov is Academic Director of Cantorial Training at Abraham Geiger College in Potsdam and Professor for History of Jewish Music at the University of Music Franz Liszt Weimar