Visiting the heritage of the Templers, German Christian pioneers, living, working and thriving in the Land of Israel more than a century ago…

© Librabry of Commonwealth

This Bethlehem is not full of pilgrims or souvenir merchants or the sound of Palestinian pop music. This is not the famous Bethlehem where Jesus is said to have been born, but Beit Lekhem ha-Glilit, Bethlehem of Galilee, a village beside an oak forest between Haifa and Nazareth in northern Israel. Its well-preserved stone houses were built by German Templers who settled here more than a century ago. They were dairy farmers and their community survived until the Second World War. Now the village is a moshav, a cooperative agricultural community, founded in April 1948. It has restaurants, art galleries, guest houses and an herb farm, and attracts tourists seeking tranquility in the countryside.

The Templers emerged from the Pietist movement in the German state of Württemberg and saw themselves as “living stones” of “a spiritual house”.

While Christians believe Jesus was born in the other Bethlehem, some archaeologists and historians think it more likely he was a native of this one near Nazareth in Galilee. Bethlehem of Judea, the city of King David, is only named as Jesus’ birthplace in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. The earlier Gospel of Mark calls Nazareth his hometown.

Did the young Templers who settled in Beit Lekhem ha-Glilit in 1906 think this Arab village was the birthplace of Jesus?

Just a few kilometers away, another colony, Waldheim, was established in 1907 by people who broke away from the Templer Society in Haifa and returned to mainstream German Protestantism. It is now called Alonei Abba. The colonists built a small church with a tower, not just a simple community centre. Nowadays, the moshav is something of a refuge for artists. The singer Shlomo Artzi was born there. The writer Meir Shalev spends time there. He wrote about the colony and its German founders in his novel Fontanelle.

A success story

The traces of the German colonies here in Emek Yisrael and elsewhere in Israel – Haifa, Tel Aviv and Jerusalem – are intriguing. What was the movement all about? As the Israeli historian Jakob Eisler puts it, “in the second half of the 19th century, Christians from various countries and nations wanted to resettle to the Holy Land, which had been under Turkish dominion for more than three hundred and fifty years. In the 1850s the first attempts by colonists from Wuppertal failed after eight years; attempts by colonists from Philadelphia failed after four. And another attempt at colonization by Americans from Maine between 1865 and 1867 also failed… The only Christians who succeeded in settling permanently in Palestine were the Templers from Württemberg.”

They established thriving colonies in Haifa (1868), Jaffa (1869), Sarona (1871) and Jerusalem (1873) and after Kaiser Wilhelm II’s visit in 1898 Wilhelma (1902) and then Bethlehem in Galilee in 1906.

The first German colony was in Haifa. Historian Alex Carmel writes: “In those days, Haifa was still a miserable place, overshadowed by Acre, the district capital. Most of the 4,000 inhabitants lived crowded within the city walls. If there was anything like a fresh breeze to be felt in the small town at that time, it was the German settlers who now provided a decisive impetus for its development.”

After Haifa, further colonies were established on the initiative of Christian Hoffmann and Georg David Hardegg. The German Colony at Emek Refa’im in Jerusalem is now one of the city’s most fashionable neighborhoods. In 1871, Matthias Frank from Neuffen bought a tract of land there and built himself a house and a steam-powered flour mill. Merchants, hoteliers, craftsmen, builders and teachers soon settled there. After Hoffmann moved the Templer headquarters and college to Jerusalem in 1878, the movement was centered there.

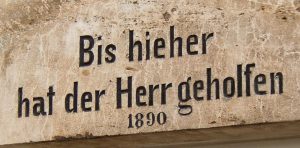

In about 1890, the Templers built a new neighborhood in a pine forest on Mount Carmel in Haifa, with residential buildings, hotels and convalescence homes. Keller House, which had been the residence of the first German consul in Haifa, Friedrich Keller, is home to the Gottlieb Schumacher Institute for Research of the Christian Presence in Palestine in the Modern Era at the University of Haifa. Schumacher was a Templer and an engineer and architect who left his mark on the city.

©Touristboard Haifa

For the Jewish settlers who started arriving in greater numbers in 1882, the Templers, about three thousand in all at the time, were at first role models and living proof that it was indeed possible for Europeans to live, work and thrive in the Land of Israel. Later, the Templers’ rather universalist faith gave way to a fervent German patriotism. In the early 1930s, more and more of them turned to Nazism. During the Second World War, Britain, as Mandate power in Palestine, interned the Templers and then either sent them to Germany or deported them to Australia. The last remaining Templers had to leave the country in 1948 at the time of the foundation of the state of Israel. Nowadays, the Temple Society is based in Stuttgart.

In the early years of the state of Israel, little attention was paid to the history of the Templers. Author Peter Finkelgruen, who lives in Cologne, wrote about two old fountains beside the little house near the beach in Kfar Samir outside Haifa that his grandmother Anna had built for the two of them in 1952: “A dissertation from 1937 is lying in front of me. It tells me that the first houses in the village were built in 1900 and that the place was then called Neuhardthof and was a German settlement. The founders of this colony had drilled a well there. […] For years I had thought we had built and lived on the terrain of what had been a Palestinian village.” Kobi Fleischmann, who lives in Beit Lekhem ha-Glilit, writes in a similar vein: “We thought the Jewish settlers before 1940 and after 1945 had created the infrastructure in this area. Now we hear that Germans were here before us, and it was upon their achievements that we could build after 1948.”

The buildings in the former German Christian settlements across Israel – homes with red-tiled roofs, schools, community centres – and their cemeteries are slowly being declared heritage sites and carefully restored. Nowadays, the former Templer colony of Sarona in the heart of Tel Aviv, with its 37 buildings, is like an open-air museum. Swedish explorer Sven Hedin wrote about Sarona in 1916: “Many plants were in blossom… They mainly grow grapes, oranges and vegetables. Like in old times – in the land of milk and honey.”