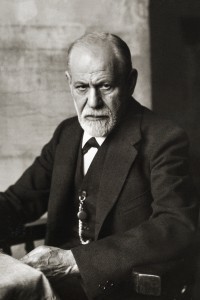

On his thirty-fifth birthday (May 1891), Siegmund Freud received a surprise gift from his father, Jakob: the Philippson Bible that Freud had studied as a child, newly bound in leather and outfitted with a Hebrew dedication calling on him to open its pages and rediscover its “wellsprings of understanding, knowledge and wisdom.” His birthday Bible languished unread until 1934, when Freud finally took up his father’s challenge to open it again, possibly because Hitler’s accession to power a year earlier had moved him to confront his Jewish identity anew. The literary result was Moses and Monotheism, Freud’s only ostensibly Jewish book.

On his thirty-fifth birthday (May 1891), Siegmund Freud received a surprise gift from his father, Jakob: the Philippson Bible that Freud had studied as a child, newly bound in leather and outfitted with a Hebrew dedication calling on him to open its pages and rediscover its “wellsprings of understanding, knowledge and wisdom.” His birthday Bible languished unread until 1934, when Freud finally took up his father’s challenge to open it again, possibly because Hitler’s accession to power a year earlier had moved him to confront his Jewish identity anew. The literary result was Moses and Monotheism, Freud’s only ostensibly Jewish book.

Other than that work, Freud never addressed his biblical heritage; but he had a lot to say about ritual, and he knew Jewish ritual well,in particular the seder, which had taken the place of the ancient Passover sacrifice, which, the Torah insists must be done “in accordance with all its rules and rites,” Freud did not have these instructions specifically in mind when he wrote his treatises on religion, but he would gladly have cited them as evidence of his claim that religion is a caricature of obsessive-compulsive neurosis. The very nature of ritual is that it must be done “just right” – which was, of course, Freud’s very point.

Still, Freud was not altogether objective in his critique. Lots of things, not just religion, are done “just right,” including Freud’s own writings which follow very strict canons of scientific research and argument. In the government of Freud’s Vienna, everything followed exact bureaucratic specification. And if Freud had consulted his own physician, lawyer, or accountant, he would have noticed all due attention being paid to detail.

As to ritual, whatever academic conferences Freud attended were nothing, if not ritually determined as to such things as who gave papers to whom; and who responded and how. Indeed, the psychoanalytic method has itself been described as a highly ritualized process. It was not, therefore, ritual that Freud found objectionable so much as it was religion, which he had rejected long before he applied his psychological theory to it. Freud’s commitment to scientific secularism had no room for religion, and as time went on, Freud developed theories that justified his objections.

Do the Rite thing!

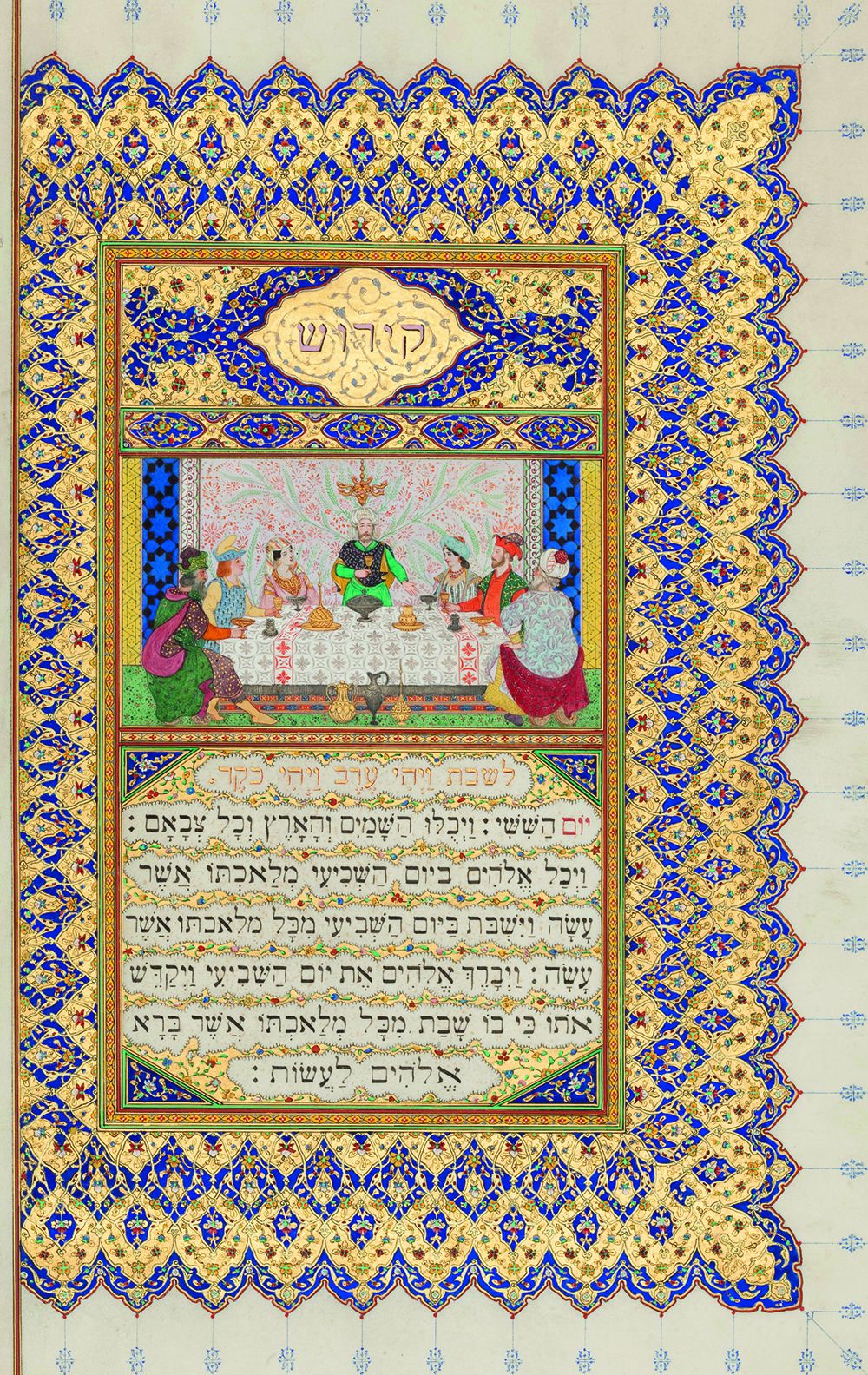

But Freud was a genius and a doggedly accurate observer of human behavior; he was not, therefore, altogether wrong. Sometimes religious ritual does approximate obsessive-compulsive disorder. An example is the way some medieval Jews interpreted the phrase, “in accordance with all its rules and rites.” The 11th-century rabbi, Joseph Tov Elem (or Bonfils, his French surname), incorporated the line into a pre-Passover synagogue poem that highlighted the importance of attending to every detail of Passover preparation. One verse of that larger composition still concludes our Haggadah: “The Passover celebration has concluded appropriately,” we say, “in accordance with all its rules and rites.”

Bonfils had internalized an attitude that pervaded Christian circles in his day: the idea that religious rites (like baptism and Eucharist) achieve their intended impact as an automatic consequence of punctilious attention to detail. By contrast, skipping a single step or doing anything out of order renders the ritual null and void, so at roughly the same time that Bonfils was writing his poem, other rabbis were developing mnemonics to guide Seder leaders in doing everything “just right.” We still have one such mnemonic today: Kadesh urchatz, by Samuel ben Solomon of Falaise. We chant it as the Seder begins just to anticipate what follows, but originally, it was used to guarantee that the Seder not be rendered worthless on account of an error in order.

In its time, this was indeed an obsessive-compulsive attitude, but it is not typical of the mainstream Jewish approach to ritual over the years. Even “in accordance with all its rules and rites” was interpreted to mean more than an obsessive concern for sacrificial detail. Both Rashi and Ramban, for example, think it also entails linking the ritual acts of the Passover sacrifice to the non-ritual aspects of the Passover message — eating unleavened bread, for instance, as a recollection of the haste with which Jews departed Egypt so long ago. Elsewhere, too, the impact of halachic action is not normally believed to follow magically as a consequence of doing it flawlessly.

Of course we perform our rituals “properly.” Otherwise they would not be rituals. But everything that matters deeply to us gets done that way: arranging an anniversary evening, perfecting a golf swing, posing for an important photograph, creating a beautiful dinner: these are all examples of making sure that details do not get overlooked. Far from being obsessive-compulsive behavior, these are instances of artistic enterprise.

The lesson of it all — from the biblical Passover sacrifice to the Seder of today, and every other ritual we have as well — is that human beings have an artistic impulse at our very core. We describe God’s original act of creation as artistry; and we have been partners with God ever after. We love harmonized melodies, complementary color schemes, matching clothes, flowing language, and even coincidences that suggest patterns behind pure randomness. We should conclude (contra Freud) that while people can use ritual to further their own obsessive-compulsive needs, most of us appreciate it for its artistry — the means to express ourselves through what is graceful, elegant, beautiful, and profound. Ritual is the regularized affirmation of order that matters; Inherited rituals are reminders of the shapes other people saw. Our ancestors saw patterns we should not want to do without. Even the lowly motsi, the blessing we say over bread, should be a metaphoric means of dreaming in league with God.

Rabbi Lawrence A. Hoffman, PhD, is professor of Liturgy, Worship and Ritual at the Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion in New York City.