The Omer calendar helps us appreciate the value of each day in the seven weeks between Passover and Shavuot so that “we may obtain a wise heart”…

© Public Domain / Wikimedia

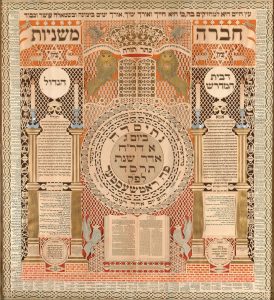

Omer Calender and Memorial Tablet, papercut by Baruch Zvi Ring

The creed of the Jew consists of his calendar,” wrote Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808–1888). One feature of the Jewish calendar is to count out loud and publically each day between Passover and Shavuot, beginning on the second night of Passover, or Pesach. Right now, in the seven weeks between the two Jewish festivals, the biblical mandate to “count the omer” (sefirat ha-omer) implores us to count the days which link the exodus from Egypt with the giving of the Torah: “From the day after the Sabbath, the day that you bring the sheaf of wave-offering, you shall count off seven full weeks.” (Leviticus 23:15).

This ancient tradition is rooted in agricultural tasks of reaping and bringing sheaves of barley to the Temple in Jerusalem. An omer is a unit of measure which was offered at the begin of these seven weeks, hence the name. The Book of Leviticus opens with a detailed description of the sacrifices brought by the ancient Israelites. With the destruction of the Temple in 70 BC, these practices were completely abandoned. In the process of transformation of the Jewish religion, the counting of the omer took on a symbolic and meditative flavor. When we do so, we cherish the days that span the time from the liberation from Egyptian slavery to our spiritual liberation. A special omer calendar helps assure that the proper count is kept and gives the appropriate formula for the blessings of each day.

The splendid papercut work on this page, created by Baruch Zvi Ring in 1904, combines a monumental memorial plaque for the deceased members of the Mishna study society of Rochester, New York, with a traditional omer counter. The two outer circles of the center field are the calendar. The first holds the blessing said nightly at the counting and the formula for the first night; the outer band of roundels contains formulas for the remaining forty-eight nights, traveling clockwise and specifying each day’s count. With reference to Shavuot and the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai, the Ten Commandments prevail over the commandment of counting omer, flanked by two protective lions and the crown of Torah.

Rabbi Hirsch, the founding father of Neo-Orthodoxy in Germany in the 19th century, explains why Pesach coincides with spring: “The festival of our historical revival must also be the festival of the revival of nature. The God whose breath of spring awakens nature from the death-like numbness of winter is the same God who delivered us from death and bondage and granted us life and freedom.” Shavuot complements Pesach as the responsibility that comes from liberation, and the idea of counting each day represents spiritual preparation and anticipation for the giving of the Torah.

Reform Judaism had dropped the counting of the omer generations ago, but as Rabbi Michael Shire suggests, it might be time to bring it back: “On our journey from Pesach to Shavuot, we symbolically walk away from the things that oppress us … If the rituals of our tradition, ancient and modern, can assist us to do so, then they will have fulfilled their function,” says Rabbi Shire, who serves as professor of Jewish education at Hebrew College. “Counting of the omer may seem one of those strange anachronistic Jewish folkways, but it may just be another way to understand ourselves and our journeys through life arriving at Shavuot in order to let the Torah come to us in a new and inspired way.” Like Baruch Zvi Ring’s splendid artwork, that truly would be beauty within beauty.■