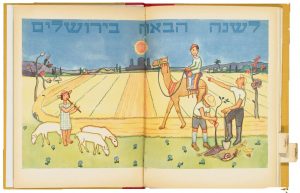

“Next year in Jerusalem” – this wish at the end of the Seder is an expression of a yearning that has been preserved for more than 2,000 years…

Passover, which just ended on April 18, is the first of three festivals of pilgrimage during which Jews, both during the time of the Temples and in the later Diaspora, made an annual pilgrimage to Jerusalem. The Passover festival recalls the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, an event which also marked the emergence of the Israelites as a people. It was King Hezekiah who renewed the Passover feast, upon which “there was great joy in Jerusalem” (2 Chron 30: 25-26).

On Passover eve, we recount the Haggadah which tells the story of the Exodus and says, “Whoever is in need, let him come and conduct the Seder of Passover. This year we are here; next year in the land of Israel. This year we are slaves; next year we will be free people.” Ever since the Middle Ages, the Seder evening ends with the phrase “Next year in Jerusalem.” This wish is an expression of a yearning that has been preserved for more than two thousand years. And the yearning also has an eschatological element: according to Isaiah 22, at the “end of the earth” all people will go to Jerusalem to greet the Kingdom of Peace.

It was the Viennese Rabbi Shalom of Neustadt (who died around 1415) who incorporated the Hasal Seder Pesach, a poetic compilation of all the rules of the Seder evening, as the culmination of the festival liturgy. From his student, Isaac of Tyrnau, who was born in Vienna, we know that initially it was customary to say “next year in Jerusalem” immediately before Hasal Seder Pesach. The phrase was first mentioned in Rabbi Tyrnau’s “Book of Customs” (Sefer ha-Minhagim), suggesting that by the late 14th century it had become customary in the Duchy of Austria, the Kingdom of Hungary, and Styria.

Around the world, when Jews celebrate Passover, they conclude the Seder with the wish “L’Shana Haba’ah B’Yerushalayim.“ In so doing, we recall the journey that brought us from Egypt to Jerusalem. The Hebrew name for Egypt is Mizrayim, which can also mean “boundaries,” “limits” or “restrictions,” while Yerushalayim means “City of Peace.” The path to Jerusalem thus leads from the concrete to the abstract; from the profane to the holy.

But what do we say if we already live in Jerusalem? With the settlement of more and more Jews in the Land of Israel in the 19th century, it became traditional to end the Seder by exclaiming “Next year in the rebuilt Jerusalem.” This expression, for example, was employed in the 1920s by the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook.

However, the phrase Yerushalayim ha-Benuyah does not presume the construction of the Third Temple and the re-introduction of the sacrificial service. Rather it is our duty to work for a better Jerusalem, the Jerusalem of our ideals. This is the Jerusalem envisioned in Israel’s Declaration of Independence – of a state based in “freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel.” Next year in Jerusalem? If we take the social obligation articulated by the prophets seriously, we will have taken a further step toward making this hope a reality.