The Jewish Experience of World War I

I am still ok and living”, wrote Australian Jewish soldier, 18-year-old Idey Alexander, from the French battlefields to his sisters in Melbourne in the days following the Armistice of World War I. This summer, exhibitions, symposia and book launches mark the 100th anniversary of the beginning of the Great War. Quite a number of them describe the war as a pivotal time of change for the Jewish community in Europe and far beyond. In Germany, the Jewish Museums of Munich and Berlin address the historical event of WW I from a Jewish perspective. The focus is on the experiences of Jewish German soldiers and their families between 1914 and 1918. Through letters sent from the front, diaries, photographs, and other personal objects, they explain the everyday life of war. The patriotism of many German Jews and their war effort also play a role. One rich source is an extensive collection of 748 letters from the warlines written by 77 pupils of the Reichenheim Community Orphanage to the director, the philologist Dr. Sigmund Feist. “I see no parties anymore, I see only Germans,” Kaiser Wilhelm II proclaimed on August 4, 1914 in his speech from the balcony of Berlin’s Royal Palace. Five weeks before in Sarajevo, the Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip had gunned down the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie. The assassination sparked the July Crisis, which would culminate in the start of the first modern war of mass destruction. The total number of deaths would include about 10 million military personnel and about 7 million civilians. Regardless of their party affiliation or religion, the German people followed the call of their head of state. They included – as in 1813 and 1871 – members of the Jewish faith as well.

Love of the fatherland

‘“German Jews! In this hour we must demonstrate anew that we Jews, proud of our tribe, belong to the best sons of the fatherland. The nobility of our four-thousand-year history obliges us to do so. We expect our youth to rally to the flag with joyful hearts,” the Jüdische Rundschau newspaper wrote in its leader after the Kaiser’s proclamation. Although German Jews had officially enjoyed equal rights, enshrined in the constitution since 1871, familiar old stereotypes and prejudices within society remained practically unchanged. The First World War was therefore the next good opportunity for German Jews to show that loyalty and love of the fatherland did not depend on one’s religious creed. In the following four years 96,000 of them fought at the front. 12,000 were killed and 30 percent were decorated.

Pastoral care

But egged on by anti-Semitic organizations and parties, during the war the opinion grew within the German officer corps that the Jewish community was shirking its duty to take up arms. “Everywhere their faces are grinning, except in the trenches,” and “In Berlin one sees only cripples and Jewish boys,” some propagandistic accusations claimed. The letters of Professor Max Rothmann demonstrate that the opposite was true: With the intention of enlisting his underage son in the Prussian corps of cadets, he wrote to the War Ministry to “devote our energies to the Fatherland above and beyond the call of duty.”

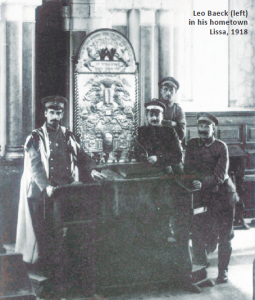

In October 1916, the German General Staff ordered a census of all Jewish soldiers in the army to determine how many actually served on the front line. The fabricated census was publicized with great fanfare, suggesting that the Jews were not fulfilling their obligations. The actual results showed that Jews fought in disproportionally large numbers on the front lines, but this was never released to the general public. However, Jews in the German army were generally not victimized by anti-Semitism, concludes the US rabbi David J. Fine in his dissertation Jewish Integration in the German Army in the First World War. “I find that Jewish soldiers found integration and that anti-Semitism was not a significant factor in their war experience. Theirs was a war where they found themselves as Jews, men, soldiers and Germans, fighting for a future that might have been,” he says. Field rabbis such as Leo Baeck (1873–1956) reflected the presence of German Jewish soldiers at the fronts of the First World War. The conflict saw the establishment of an institutional Jewish pastoral ministry in the field, alongside the Protestant and Catholic ones. Besides providing actual religious pastoral services, the main tasks of these field rabbis included distributing religious literature and “love donations” from back home, conducting entertainment evenings and lectures and serving in field hospitals. With the introduction of their military pastoral care the Jewish communities and organizations also hoped that more of German society at large would recognize the efforts of the Jewish community and its faith. Viewing the development of society after the war, it becomes clear that the system of Jewish pastoral care represented only an episode in the history of Jews in Germany. But its importance points to a level of integration and emancipation for the Jewish minority that had never been achieved before. Caught in conflict between belonging and exclusion, the First World War provides a central reference point for German-Jewish commemorative culture. “Public memory of the sacrifice of German-Jewish soldiers in the Great War has been gradually subsumed into the much greater catastrophe of the Holocaust,” says historian Tim Grady. “It was only in the late 1950s that both Jews and other Germans began to rediscover and to re-remember this largely neglected group.” ■

Further reading:

On field rabbis see Feldrabbiner in den deutschen Streitkräften des Ersten Weltkrieges

See also the highly informative catalogue of the exhibition at Munich Jewish Museum: WAR! Jews between the Fronts 1914–1918.

Both published by Hentrich & Hentrich Verlag Berlin.