Abroad majority of Germans is decidedly opposed to Eurobonds, the government bonds issued jointly by the Member States at a standard interest rate, for which the euro area states would be collectively liable. However, an increasing number of European states support the introduction of these joint bonds. Among the idea’s proponents are the new governments in France as well as those in Athens, Rome and Lisbon and various EU bodies.

Abroad majority of Germans is decidedly opposed to Eurobonds, the government bonds issued jointly by the Member States at a standard interest rate, for which the euro area states would be collectively liable. However, an increasing number of European states support the introduction of these joint bonds. Among the idea’s proponents are the new governments in France as well as those in Athens, Rome and Lisbon and various EU bodies.

This attitude arises in part from a self-serving calculation of national interests. Currently, countries like Spain and Italy must pay nearly 7 percent on 10 year bonds. Germany pays about 1.4 percent – that’s half a percentage point less than the current rate of inflation. And for the first time in Germany’s history, it even seems possible that zero interest will be paid for two-year federal bonds. When Germany’s European partners have to pay three times as much in interest in order to secure new capital, that is a clear vote of noconfidence from the financial markets. The high interest rate severely limits these states’ room for maneuver in terms of financial policy, restricting their ability to pay down their debts and making a Keynesian stimulus program virtually impossible.

The rewards of unification

In contrast, Germany is now reaping the rewards for its own austerity policies over the last 10 years in the form of additional fi nancial leeway even allowing it to consider tax cuts during a fi nancial crisis. However, if Germany accepted Eurobonds, which would require a unanimous vote to amend the Treaty, then the interest on German debt would increase. Based on solid estimates, this would lead to an average interest rate of 3 to 4 percent, or double Germany’s current annual interest rate if the maximum fi gures are used in the computation. In what country in the world would political leaders or citizens accept such a decision? None of the heads of state having gathered at the G20 meeting in Mexico would have opted for it either. Effectively, it would mean a solidarity tax on the income of German citizens.

Something like this, however, has already occurred. Essentially, the introduction of the euro falls into the same category. After that, Eurobonds are merely a déjà vu. Today, the future of the euro area – and maybe even the European Union – is at stake. When the euro was introduced, it was another matter; Germany needed its European partners to agree to German reunification.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, which separated the democracy of the Federal Republic of Germany from the communist German Democratic Republic until November 1989, it was clear to see that Germans from both East and West wanted reunifi cation. Many countries in Europe viewed this prospect with trepidation, or at least discomfort, given the experience of two world wars. Britain’s then-Prime-Minister Margaret Thatcher was against reunifi cation. Her Italian counterpart Giulio Andreotti remarked sarcastically, “I love Germany so much that every day I give thanks that there are at least two of them.” President Mitterrand of France was also against German unity. In 1989, he traveled to East Berlin, where he tried to convince the communist leadership of East Germany to preserve their independence. His efforts were in vain. The people had turned their back on the Socialist Unity Party and the state. One of the catchiest slogans heard at the Monday demonstrations in Leipzig was: “If the Deutschmark comes to us we’ll stay, if it doesn’t, we’ll go away.” The exodus from the former GDR brought the economy to its knees. There was only one way for the leadership in East Berlin to prevent an economic collapse, and that was to join with the economically stable West Germany. Given West Germany’s size – three times that of East Germany – its economic strength, and the fl agging economy of the GDR, it was clear that the East would not be calling the shots in this merger. The leaders of East Germany regretfully informed Mitterrand of this fact. The decision reached shortly thereafter, to exchange East German marks for Deutschmarks at a rate of 1:1, was the fatal blow to the SED-state’s economy. It ended East Germany’s membership in the Eastern Bloc economic zone, Comecon.

Birth of the euro

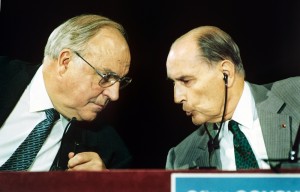

François Mitterrand tried to make the best of the situation. The clever Frenchman knew that Helmut Kohl, Chancellor of West Germany, would seize the moment and push for swift reunifi cation. Kohl, a savvy accumulator and wielder of political power but an economic layman, was willing to pay almost any price for reunification. Mitterrand was determined to exact the maximum price – the relinquishment of the Deutschmark and the end of Europe’s subjugation to the guardianship of the German Bundesbank. In exchange for Paris’s consent to German unity, he demanded that a European currency union be swiftly implemented. Kohl agreed without recognizing the far-reaching consequences this would have for Europe.

François Mitterrand tried to make the best of the situation. The clever Frenchman knew that Helmut Kohl, Chancellor of West Germany, would seize the moment and push for swift reunifi cation. Kohl, a savvy accumulator and wielder of political power but an economic layman, was willing to pay almost any price for reunification. Mitterrand was determined to exact the maximum price – the relinquishment of the Deutschmark and the end of Europe’s subjugation to the guardianship of the German Bundesbank. In exchange for Paris’s consent to German unity, he demanded that a European currency union be swiftly implemented. Kohl agreed without recognizing the far-reaching consequences this would have for Europe.

The currency union, in effect since 1999, with euros in circulation since 2002, had a grave birth defect. The euro area members shared a currency, but their financial, taxation, and economic policies remained largely uncoordinated. Nevertheless, interest rates for government bonds issued by all the countries in the euro area converged. The markets assumed the existence of a transfer union. After all, the economic powerhouse Germany and the shared will to “perfect the house of Europe” were there to back up the euro.

The illusion created by the interest rates functioned like an enormous economic stimulus program. Italian, French, Greek, and Spanish bonds paid dramatically lower interest rates than they had previously. Although their debts were mounting, these countries had to pay less to service them. The result was not greater discipline in the euro area, but instead a “horn of plenty” policy based on which government largesse fl oated down on the citizens of Europe. Saving and enhancing competitiveness were no longer on the agenda. Instead, consumers binged, real-estate bubbles expanded, and outdated economic structures persisted. While Germany had to raise two trillion euros for the “burdens” of reunifi cation, the “Club Med” states like Greece and Italy wasted a large share of the money they had raised through cheap loans granted to their states.

If Eurobonds are introduced, they could have many similar effects. It was hardly surprising that the government debt held by these states made a quantum leap, and then worsened with the fi nancial crisis in 2008 and the banking crisis.

Given this history, can the Germans really be blamed for their reticence to once again serve as the guarantor of the stability of the Eurozone? Should we give the debtor states the cold shoulder – not just out of economic self-interest, but based on our historical experiences? Even the most naive of savings account holders won’t be happy to pay the debts of wastrels a second time around.

An economy based on exports

There is a great deal of evidence that German-style austerity is the right path for Europe’s further development. Financial policy in particular must exert real pressure for fi scal discipline. The unconditional issue of Eurobonds would certainly weaken this. However, we must not forget that Germany also profi ted immensely from the low interest rates given in the current debtor states. Germany’s economy is based on industrial exports – in other words, it needs buyers for its goods. One can certainly raise doubts as to whether the BRIC states are really a more reliable alternative over the long term. A collapse of the euro system is not in Germany’s interest either. We also cannot forget that Germany agreed to the currency union in full awareness that it entailed enormous risks if a corresponding fi scal union was not enacted.

It is an irony of history that Mitterrand’s dream of an end to German hegemony in monetary policy has been turned on its head. Without Germany, there will be no solution to the debt crisis. There may be no solution with Germany, either.