Aharon Appelfeld’s new novel is a story of survival through language

Aharon Appelfeld’s new novel is a story of survival through language

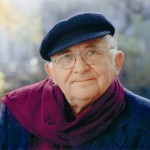

Aharon Appelfeld turned 80 years old early this year. It is a miracle that he is alive. His mother was murdered by anti-Semitic Romanians. Nazis murdered his father in a concentration camp in Transnistria. How did he survive? He hid in the forest, concealed his Jewish identity in the Ukraine (because he was blond and blueeyed) and joined the Red Army as a kitchen boy. Appelfeld must have a very powerful survival instinct.

For him, survival means leaving nothing untried. And life? For him it means to write. His books are often based on variations of his own story. They tell of people who, like him, survived the Holocaust, and how the

y did it. In his latest novel, which was published in Israel in 2010 and only recently came out in German translation, Appelfeld describes how writing and language can save a young Holocaust survivor. Erwin’s story resembles Appelfeld’s. A love of language gave both their lives new meaning. This book pulls readers in from the very first sentence.

Endless tiredness

Of course, we’ve all read a number of books about the post-war period. Many dealt with the experience of Holocaust survivors – their disorientation, the doubts they felt, their efforts to regain the strength to live. However, no novel that sets in shortly after World War II has begun by pointing out that the protagonist is tired. Reading the fi rst sentence of this book, it dawns on you immediately – of course the survivors must have felt, first and foremost, tired! They had had to fi ght for their lives every day. Every day they had been consumed by the fear of annihilation. Finally getting some sleep – that is what drives Erwin, the boy who lost his parents and does not know where to go. “Since the end of the war, I’ve lived in a state of endless tiredness.” Thus begins Appelfeld’s book about “The Man who Never Stopped Sleeping.”

It is Appelfeld’s most affecting novel. Its sentences are plain and incisive. They tell of longing, mourning, and loss, but also of dreams. They never veer into kitsch, because Appelfeld writes with a tenderness that contrasts strongly with Erwin’s fate – the fate of the surviving Jews. Mirjam Pressler’s fantastic translation from the Hebrew is likewise tender and melodious. Her achievement in rendering Appelfeld’s tone in German is worthy of the highest accolades.

A new person

The man who could not stop sleeping is actually a 16-year-oldboy. The National Socialists have been defeated. The war has torn Europe apart, and in the middle of this chaos we meet Erwin, the fi rst-person narrator. His own body protects him from the chaos: wherever he goes, he is overium come by sleep – in horse-driven carriages, in trains, on trucks. He journeys from dark northern Europe to light-flooded Naples with his eyes mostly closed. Other refugees carry him when he has nodded off. Later, after Erwin has lived a long time in Israel and is no longer named Erwin, but Aharon, he sometimes meets people who remember him and say, “You were the sleeping boy!”

In his sleep, Erwin reclaims the world that no longer exists. He speaks to his mother, and he visits his father, an unsuccessful writer. The longer Erwin crams Hebrew in Naples, with the power of the new language shoving his old native tongue aside, the more worried his parents become in his dreams. At some point, they no longer understand him. Erwin becomes a new person, just as the founders of the State of Israel had intended. Yiddish is not to be spoken, but modern Hebrew. The children of the Holocaust survivors want to separate themselves from their parents. They found a Zionist group, work out until their muscles bulge and tan their skin. The new person shakes off his past as a victim. Erwin too. But Erwin has a hard time accepting this new role. He is torn between the old and the new world, between Europe and Palestine, where the new State of Israel will soon be founded.

Appelfeld takes us on a fascinating journey. Through the eyes of 16-year-old Erwin we leave the rubble of post-war Europe behind and travel via Italy to Palestine, into the light – and Erwin is at first blinded by his new life. “Now, I felt like I was being thrust into a painful brightness.”

In southern Italy, at a training camp led by Efrajm, a Jew from Palestine, Erwin submits to a strict daily regimen. It consists of rowing, long-distance running, and gymnastics. In between, they drill Hebrew vocabulary. “Within three months, you will be different people,” the youth who are to build Israel are told. “They won’t recognize you, tall, powerful, and tanned. And your bodies will be one with the language.” The new language fascinates Erwin. But it is too unwieldy, too foreign for him. Someday, he will be at home in it, but he still copies every word of the Hebrew Bible in order to lose his fear of the letters. His father had been a writer, but the manuscripts he sent to publishers always came back with a polite thank you. In Israel, Erwin will achieve what his father could not. He will publish books.

Becoming a writer

In one of the dream sequences, Erwin speaks with his mother. He confesses that he is leaving her language behind, that he is learning “the language of the sea,” the language that one “learns on the beach, that has a word for each of its colors and smells.” His mother asks, “What do you need the language of the sea for?” Erwin wants to get away from the refugees, from the “darkness” and the “gloom”. He and his friends run along the beach in the mornings and when they return from their long-distance runs, “We went past the barracks and heard how the other refugees conversed with one another in their native tongues. They were still living in the Ghettos and the camps.” When Erwin becomes Aharon and travels by ship to Palestine, he realizes, “Hebrew is sinking into me, deeper and deeper.”

The days in Palestine are long. They begin at 6:00 am and end at 11:00 pm. This is life on the Kibbutz, facing the future, leaving the past behind. They build terraces for orange trees, continue learning Hebrew, and they are always on guard. During his fi rst deployment, fi ghting Arab neighbors, Aharon is so badly injured that he remains in the hospital for months and has to endure eight operations on his legs. During his endless stay in the hospital, his desire to become a writer takes shape. He is still copying every word from the Bible, and he uses the words to erect a home.

First success

After enduring the eighth operation and relearning how to walk, he moves into a small apartment in Tel Aviv. There, a woman cares for him who hardly speaks, but who can read his thoughts. This is where Aharon begins to write. His writings are small experiments in a new life. He has some success: “An evening, in which I succeeded in writing a few lines, even if they were clumsy, was an evening full of light.” It is poetic sentences like this one that make this book so worthwhile to read. After fi nishing the 70 episodic chapters, you will wish there was a sequel.