Frankfurt’s Goethe University celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. It was the first institution of higher learning established solely through a citizens’ foundation. Many of its founders, benefactors and faculties had a Jewish background. A similar foundation gave rise to what is probably the university’s most famous branch: The Frankfurt School.

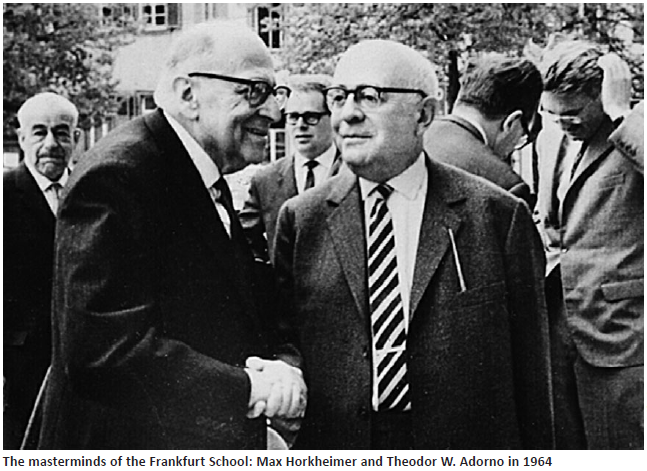

On October 18, 1914, Frankfurt University opened its doors. Its statutes expressly banned any form of discrimination. Whereas Jewish professors were being turned away from other universities, in Frankfurt they constituted a third of the faculty. The institution’s intellectually liberal spirit also attracted a circle of young, gifted, left-leaning academics. They included the psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, literary scholar Leo Löwenthal, political scientist Franz Neumann, economist Friedrich Pollock and social philosopher Max Horkheimer. In 1931 the latter became director of the Institute for Social Research, founded in 1924 by the Jewish philanthropist Felix Weil. This was where the Freudian-Marxist discipline of Critical Theory, also known as the Frankfurt School, was born.

Messianic expectations

These young theorists would be joined later by the likes of Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse, all of whom were scions of assimilated Jewish families. Although these young scholars didn’t identify as religious, messianic expectations found acceptance in their thought.

Looking back, Horkheimer admitted to having hidden religious and moral impulses that were certainly denied during his early years. Nonetheless, unlike basic Marxism, Critical Theory dealt seriously with religion and metaphysics.

The practical political goal of the Frankfurt School of helping establish a “liberated society” came to nothing. The Nazis came instead. But, as Löwenthal once said, Critical Theory ultimately saved the lives of Horkheimer’s circle. The group’s research on the “psychological condition of workers and employees” found that the people tended to think as reactionaries, not progressives. And so, by January 1933, Institute chief Horkheimer had already made all precautions to rescue lives and foundation capital. Most of the Institute’s members fled to the US.

Closed by the Nazis

On the day the Nazis seized power, Horkheimer’s house was searched by the SA. His Institute was closed in March. The Nazis quickly installed Ernst Krieck, a fanatical party member, as Rector of the Goethe University and revoked every Jewish professor’s teaching license.

Four years after the collapse of Nazi Germany, Horkheimer and Adorno returned to Frankfurt. In 1951 the Institute was reopened, and Horkheimer was elected Rector of the Goethe University. The vast majority of the Institute’s members remained in the US and pursued their own careers there. Despite some tensions, Critical Theory gradually became a vehicle for transatlantic dialogue.

Chief theoretician of democracy

Its personification was Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s best pupil, Jürgen Habermas. He took substantial elements of Anglo-Saxon Pragmatism and Speech Act Theory and, with his “Theory of Communicative Action,” became the chief theoretician of Western democracy. The Frankfurt School parted company with its social revolutionary tendencies during its exile years. Thereafter it became an exclusively leftist liberal reform project.

Habermas, now 85, does not tell his students in China or Iran that all is well in Western democracy. His chief points are to defend the living world against its “colonization” by power, money and technology, and second to fight against institutional tendencies to deprive people of their rights of participating in and helping shape their democratic environment.

Axel Honneth, today’s Director of the Institute for Social Research, says Critical Theory is experiencing an “odd currency.” His students are still fascinated today by criticisms of a “completely economized existence,” finding that especially Marcuse and Benjamin provide points of departure for contemporary efforts at emancipation.

Jewish traditions were cut

But what about the Jewish traditions in Critical Theory? They were cut short brutally in the Holocaust. Adorno and Horkheimer were only two leading minds who returned to Germany from exile. Walter Benjamin died whilst fleeing from the Nazis. The broad base of Jewish culture in Germany which once spawned Critical Theory no longer exists.

The current faculty at the Frankfurt School does not include any Jews. Does this have an effect on its content? Yes, says Honneth. “The historical and philosophical intellectual motifs that decisively marked early Critical Theory no longer play any part.” Over the years, the fascinating social philosophy of Horkheimer and Adorno has become just dry social science. ■

Dieter Sattler is the head of the politics section of the daily Frankfurter Neue Presse.

He wrote his Ph.D. on Max Horkheimer