Long priding itself on its Jewish roots and tradition, soccer club Eintracht Frankfurt is now beginning to confront unsavory facts from its past…

Alongside Bayern Munich and Ajax Amsterdam, Eintracht Frankfurt was considered a “Jewish club.” Some 25,000 Jews lived in Frankfurt during the Weimar Republic and more than a handful of them were fans and even played on the squad. Many were killed by the Nazis.

With the help of the Fritz Bauer Institute, Eintracht is now trying to discover more about the fate of its Jewish members. Public interest is strong, and tours of the city demonstrate the subject’s abiding popularity. Not long ago, an audience of nearly a hundred people listened to a talk held by Helmut “Sonny” Sonneberg on the topic. Born in 1931, the longtime Eintracht fan and soccer player was only able to join the club after the war. As a young boy, Sonneberg watched with his own eyes as Jews lost their rights, and witnessed the Kristallnacht pogrom in Frankfurt in 1938. Helmut Sonneberg was separated from his parents, and lived for years in an orphanage. In January 1945, he was deported to Theresienstadt. “I experienced both things,” Sonneberg says. “The Allied bombardments and the concentration camp.”

Eintracht fan “Sonny”, 1959

(c) Eintracht Frankfurt Museum

After a short while, Sonneberg was liberated from Theresienstadt by the Red Army. He eventually returned to Frankfurt. In all the years he played for Eintracht, no one asked him about his history. At one point, the director of the Eintracht Museum, Matthias Thoma, found out about it more or less by chance. Sonny then became highly sought-after as an eyewitness of the past. For the Eintracht club, Sonnenberg’s story was tailor-made. Behind the scenes, however, all was not well, and not long ago, Sonnenberg decided to part ways with Eintracht. He had found out that one of Eintracht’s icons, the one-time national player, veteran chairman and honorary president Rudi Gramlich (1908-1988), had been a member of the Waffen-SS.

Although it was not a secret, this unsavory fact only became more widely known last year when new and incriminating documentation was found in the German Federal Archives. Indeed, shortly after the end of the war, the US occupation forces had identified Gramlich as a “major offender”. Gramlich was interned but released again in 1947 for lack of evidence. He was then re-classified to a lesser category of offender. Gramlich would go on to serve as president of Eintracht Frankfurt from 1955 to 1970.

The fact that the club remained idle so long, failing to revisit the history of one of its most prominent members, does not easily mesh with the club’s self-styled image as a “Jewish club” and hotbed resistance to the Nazis.

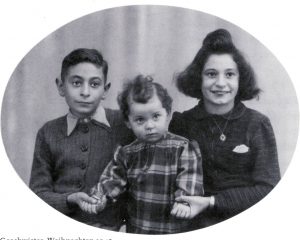

Helmut Sonneberg and his siblings, 1945

(c) Eintracht Frankfurt Museum

Now that Rudi Gramlich’s history has become more widely known, Eintracht has been forced to take a public position. A year ago, Eintracht President Peter Fischer announced that in honor of the club’s “Jewish” traditions, it would not accept any members who had voted for the far-right AfD. Eintracht also pledged to have Rudi Gramlich’s past re-examined by a team of external experts.

Another example of the amnesia that afflicted Eintracht until quite recently is the case of Julius “Jule” Lehmann. The Eintracht defender was expelled from the club in 1937. At Eintracht’s centenary celebration in 1999, the club still claimed that Julius Lehmann had managed to flee to Switzerland. This was whitewashing of history, as we now know. In reality, Julius Lehmann was deported and killed in 1942.

Helmut Sonneberg was luckier. Despite all the horrors he experienced, Sonneberg retained an optimistic outlook. Asked once about his favorite poem, however, Sonneberg gave a quote from Heinrich Heine’s Book of Songs:

“At first I was almost about to despair/ I thought I never could bear it/ But I did bear it/ The question remains: how?”■

Dieter Sattler is head of the politics section at the daily Frankfurter Neue Presse