Obsessions: Berlin’s Jewish Museum presents the drama of R. B. Kitaj, the artist, who was raised as an atheist and became one of the most interesting Jewish intellectuals of our time. Kitaj was not only a painter, but also an obsessive reader who found his diasporic home in his library

Jewish Art can be new, daring, unusual and risky”, claimed R. B. Kitaj (1932−2007) in his Second Diasporist Manifesto. This fall, the Jewish Museum Berlin is presenting the first comprehensive retrospective exhibition of the painter’s œuvre since his death five years ago. The show explores the life, legacy, and Jewish obsession of Kitaj, who was born Ronald Brooks and took the surname of his stepfather Walter Kitaj, who had fled Vienna in 1938.

The artist, who became one of the most interesting Jewish intellectuals of our time, was raised as an atheist in Ohio. His mother Jeanne Brooks was the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants, but it was the arrival of his step-grandmother after World War II that made the teenage boy start thinking about his Jewish Identity.

Pioneer of a new figurative art

Trained at Cooper Union in New York, then in Vienna, Oxford, and at the Royal College of Art in London, Kitaj became a pioneer of a new, figurative art in the early 1960’s. He found success quickly, and together with his friends Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, and Leon Kossoff, Kitaj initiated the liberation of art from abstraction, creating what became known as the “School of London”.

His transition from artist to Jewish artist was marked by the Eichmann trial in 1961 and his encounter with Jewish thought, mainly through the works of Martin Buber, Walter Benjamin, Gershom Scholem, Albert Einstein, Franz Kafka, and Sigmund Freud.

The Jewish Question

“To paint Jewish is to read Jewish”, Kitaj said. Aby Warburg’s work on iconography taught him the links between images, ideas, and articulated thoughts. By the 1970’s, “as my Jewish obsession began to unfold”, he related, “the vast literature of Jewish commentary exegesis, and midrash encouraged me to write about some of my pictures in a new spirit”.

His First Diasporist Manifesto

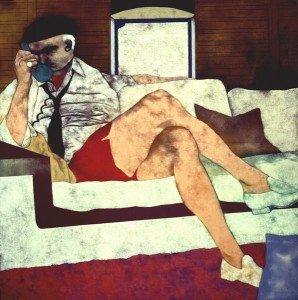

Both in work and life, he was obsessed with th “Jewish Question”, and it is this personal obsession that inspired the name for the Berlin exhibition. Soon his two passions – painting the human figure and the Jewish Question – began to converge. In 1983, Kitaj explained: “Jews and what happens to them fascinate me more than Judaism does; well, more than the God of the Jews; the phenomenal history of anti-Semitism tantalizes me far more than a faith I never knew”.

In his First Diasporist Manifesto, published in 1989, he wrote: “A Diasporist painting is one in which a pariah people, an unpopular, stigmatized people, is taken up, pondered in their dilemmas, as unsurely as Impressionists pondered the dilemmas of light or as Cubists take up perspectival and planar dilemmas.”

Kitaj often urged himself to “paint the opposite of anti-Semitism”. But what does this urge imply? He tried to grasp the persistence of both anti-Semitism and the creative cultural genius of Jewish intellectuals in the modern age. To him, homelessness was not only a permanent condition but also a pre-condition to creativity.

Capturing the history of persecution and mass murder of Europe’s Jews, and studying the phenomenon of being an outsider, he created a Jewish modern art, which he termed “diasporic”, with a rich pallet of color and with enigmatic, recurring motifs.

Diasporic home

The library became Kitaj’s diasporic home. “Very few people operationalize their reading in the way Kitaj did”, says David N. Myers, a professor of Jewish history at the University of California and founder of the Kitaj archive in Los Angeles. “As one of the great autodidacts of recent Jewish history, Kitaj followed no curriculum, just his own obsessive, iconoclastic reading”. It’s this “interpretative impulse”, as Myers calls it, that Kitaj later recognized as a “decidedly Jewish act and a practice essential to his own artistic creativity”.