As much as America had an impact on German Jews, German Jews have contributed much to America, says William Weitzer of Leo Baeck Institute…

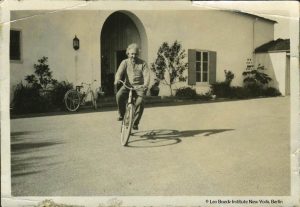

© Leo Baeck Institute New York, Berlin

The Leo Baeck Institute-New York|Berlin maintains an archive that documents the lives of Jews in Germany and throughout the German-Jewish diaspora, including Jews from German-speaking lands who played significant roles in major chapters of Jewish history and American history.

As America’s first large-scale surge of Jewish immigrants, after a small initial community of Sephardic Jews, German-speaking Jews built many of its signature Jewish institutions and gave shape to their new country. In adapting and contributing to their new home, they utilized traditions, education, and cultural ideals brought from their homelands. Their backgrounds and experiences laid the foundation for what it meant to become an American Jew.

An overview of the impact of German Jews on America might be divided into three periods: the late 18th century and most of the 19th century when German Jews were the largest percentage of American Jewry; the late 19th and early 20th centuries when German Jews continued their influential role but were outnumbered by immigrants from Eastern Europe; and, the German Jews who escaped Nazi Germany.

In the 19th century, German-speaking newcomers were one of the country’s largest immigrant groups. Roughly 5.5 million arrived from Central Europe, some 140,000 of them Jewish. As the only major country to recognize the German revolutionary parliament during its short existence (1848–49), America became a destination for immigrants and political refugees. For Jews, the allure of America was particularly compelling: they could literally emancipate themselves by stepping onto America’s shores.

Jews arriving in America from Germany brought with them a host of cultural influences and desires. Some came from a broad education shaped by Enlightenment ideals that prized Bildung, which valued self-education, critical reflection, and openness to new ideas.

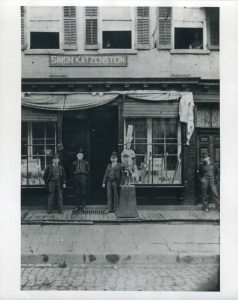

Tobacco store, 1880

(c) Leo Baeck Institute New York|Berlin

While these underlying values were German in origin, America was a perfect canvas for their expression.

Immigrants embraced the economic opportunities of America, usually with modest beginnings. They worked in trades they knew well: peddling goods, tailoring clothes, making cigars, selling cattle, horses, grain, and wine. The American economy offered lucrative opportunities for the skills and instincts that had sustained them in their homelands – entrepreneurship, making connections, and navigating from the margins of society. Many Jewish businesses took root and flourished, and Jews occupied an important place in the burgeoning economy.

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, many immigrants were eager to join the war effort. The war provided opportunity for civic engagement and for making their commitment visible to America. German Jews participated not only on the battlefields as soldiers and officers, but also in the public debates and business endeavors that shaped the war’s outcome and the era of reconstruction to follow. The Civil War brought German Jews into a passionate, national conflict and allowed them to play a role in the shaping of America’s future.

The years following the Civil War provided great visibility for German Jews in America. Many working in textiles went on to become major manufacturers, buyers, and bankers. Others opened grand shopping emporiums that reflected not only their success as immigrants but their status as Americans.

One of the trademark characteristics of German-Jewish culture in America was its association with “modern” Judaism. Many fundamental ideas for new Jewish practice were born in the German states in the early 19th century. But it was in America that the Reform and Conservative movements found exceptional opportunity.

Philanthropic muscle

When newer immigrants crowded the Lower East Side of New York City, the more established and successful of the German Jews moved to the Upper East Side where their desired social status was largely reinforced by their surroundings. Socially and symbolically, German Jews had become an established set.

By the 1890s the American Jewish community overtook that of Germany, becoming the largest center of Jewish life outside of Eastern Europe. The overall heightened status of German Jews brought with it philanthropic muscle, and many became leaders of aid societies and benevolent organizations. Philanthropic entities were created to assist Jews in need, including the American Jewish Committee founded by Oscar Straus, Jacob Schiff, and Cyrus Sulzberger to raise funds for victims of anti-Jewish pogroms in Tsarist Russia.

In August of 1914, Henry Morgenthau, a German-Jewish immigrant to America, was serving as U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. With the outbreak of World War I, Jews in Ottoman-ruled Palestine were cut off from their traditional sources of support in the European Jewish community. In response, Morgenthau immediately sent a telegram to his friend Jacob Schiff that prompted an outpouring of aid to Jews in Palestine. Subsequent pleas for help from war-torn Europe led to the founding in New York of the Joint Distribution Committee of American Funds for the Relief of Jewish War Sufferers.

After World War I, German cultural ideals and influences endured. Reform and Conservative Judaism remained forces in American religion and Jewish life. Many families of immigrant industrialists, bankers, philanthropists, and intellectuals remained influential throughout the 20th century. The ideals of Bildung – openness, self-education, and reflection – helped create a shared language for the Jewish community for decades to come.

Jacob Schiff (1847–1920)

(c) Leo Baeck Institute New York|Berlin

Like the German Jews who arrived before them, the émigrés and refugees who escaped Nazi Germany during the Holocaust brought their education, skills, and knowledge with them to America. They contributed to American society, often shaping 20th mid-century culture by combining European approaches with distinctly American modes.

Most German intellectuals who escaped from the Third Reich moved to major urban centers such as New York City and Los Angeles. Certain institutions, such as the New School for Social Research in New York City, Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, or Black Mountain College in rural North Carolina, became hubs for émigré intellectuals. Others found academic positions in universities across America, with many teaching in historically black colleges. Refugees established new organizations to help each other, and built organizations and businesses to serve as cultural, social, and spiritual homes for their fellow émigrés. The Aufbau newspaper served as a worldwide communication link.

In the United States, émigré scholars and artists were once again outsiders. They had German accents and upbringings. They were new immigrants in a new land. They were often uncomfortable in their new settings, and they sometimes encountered prejudice or bias in America as well. Nevertheless, they managed to become active participants in American cultural and intellectual life. Their insider/outsider status helped to fuel their creativity and achievements, often blending European approaches and new American priorities.

As a country of immigrants, the United States has provided opportunities for German Jews to live and prosper from the 18th century to today. Their German backgrounds combined with America’s culture allowed them to seek new opportunities for innovation and encouraged further exploration and originality. As much as America had an impact on German Jews, clearly German Jews have contributed much to America.■

William H. Weitzer is Executive Director of the Leo Baeck Institute-New York | Berlin