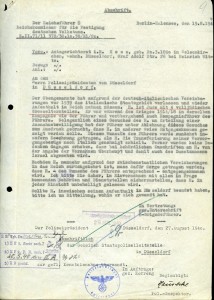

A Jew survived due to an order given by Hitler. Our editor Susanne Mauss found a note of the Gestapo to the effect that the judge Ernst Hess was not to be persecuted or deported because of an order from the Reich Chancellery. During World War I, Hess had been an officer and superior to Corporal Hitler.

Hess had the luck of being personally ‘pardoned’ by the mass killer Hitler, whose officials fulfilled his order with the same efficiency they executed their master’s mass murder decisions. Hess’ exemption only lasted until 1942 when at the Wannsee Conference the murder of the European Jews was codified. Hess survived thanks to his ‘mixed marriage’ with his gentile wife. His sister was murdered by the Nazis, as were millions of others.

Hess’ daughter is now 86 and lives in Germany. The JEWISH VOICE spoke with her and reports exclusively about the case.

They fought in the same unit in World War I. Later, Ernst Hess experienced the Führer’s personal protection – for a while. An untold story

Ever since the Third Reich collapsed in 1945, historians and journalists have been searching for written sources that might cast light on Adolf Hitler’s social and intellectual development – the mindset that ultimately led him towards the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question.”

Ever since the Third Reich collapsed in 1945, historians and journalists have been searching for written sources that might cast light on Adolf Hitler’s social and intellectual development – the mindset that ultimately led him towards the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question.”

One irony of this dark history is that Hitler could on occasion bestow his personal protection to a person otherwise marked for death. One example is Eduard Bloch, the “noble Jew” from Linz. As the family physician who treated Hitler’s mother, he enjoyed the Führer’s personal protection. On Hitler’s orders, Bloch was not touched when Austria “merged” with the German Reich in 1938, and his immunity continued until his emigration in 1940. But were there others?

A file kept by the Düsseldorf Gestapo on judge (Amtsgerichtsrat) Ernst Hess includes a letter from the infamous Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer of the Schutzstaffel (SS, Protection Squadron), which expressly grants Hess, a former comrade and company commander of Adolf Hitler in World War I, relief and protection “as per the Führer’s wishes.” This protection applied during a time when the situation for German Jews was becoming more and more dramatic. Himmler made a point of informing all relevant authorities and officials that Hitler’s war comrade was “not to be inopportuned in any way whatsoever.”

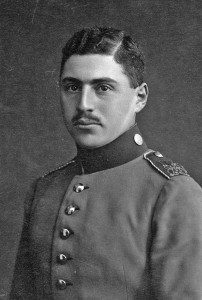

Ernst Moritz Hess, born in 1890 in Gelsenkirchen, had joined the 2nd Royal Bavarian Reserve Infantry as an officer at the beginning of World War I, the same regiment that Hitler volunteered for. Both men were deployed to the Flanders front in the fall of 1914, serving in what was known as the “List Regiment” (RIR 16) until 1918.

Decorated with the Iron Cross

Ernst Hess was seriously wounded in October of 1914 and again two years later in October 1916. In the summer of that same year, he had temporarily been Hitler’s company commander. Decorated with the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class as well as the Bavarian Military Order of Merit, he was promoted to Lieutenant in 1918. In 1934, he was even awarded the Cross of Honor of World War 1914/1918. Hess’ daughter recalls how her father returned from get-togethers with old comrades of the List Regiment in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. He would often relate to the surprise expressed by Hitler’s former comrades when they heard that the maverick politician had been in their ranks. “What, Hitler? He was in our unit? We never even noticed him.” Hess then used to explain that Hitler had had no friends within the regiment, never said a word to anyone and had been “an absolute cipher.” Hess, by contrast, had formed long-lasting relationships to his fellow soldiers. One was Fritz Wiedemann, former aide de camp to the List Regiment’s HQ and later personal adjutant to the Führer from 1934 until 1939. Via Wiedemann, he also had ties to Hans Heinrich Lammers, Head of the Reich Chancellery. These relationships would prove useful, if only for a time. Because although Ernst Hess had been baptized a Protestant, the Nuremberg Race Laws classified him as a “full-blooded Jew.”

A kind of spiritual death

Hess was the son of attorney Julius Hess, admitted to practice before the higher courts. His mother was Elisabeth, née Heertz, scion of a family of bankers from Wetzlar. Ernst Hess was married to Margarete Witte, a Protestant, with whom he had a daughter, Ursula. At first, the family settled in Düsseldorf, moving to Wuppertal when Hess was forced to retire as a judge as of January 1st, 1936. After being beaten up by SS thugs in front of his house in the fall of 1936, Hess moved his family to Bolzano, Italy in October of the following year. He had chosen South Tyrol, a German-speaking province annexed by Italy after World War I, because he wanted his eleven-yearold daughter to be educated in a Germanspeaking environment. As early as June 1936, Hess had sent a petition to Hitler, asking for an exception to be made for himself and his daughter, who was classified a “1st-degree half-breed” under National Socialist racial ideology. In his letter, Hess referred to his Christian upbringing and patriotic political outlook, as well as to his service in World War I. The sensitive Jewish judge, who played the violin and viola at concert level, gave voice to his pain by closing his letter with the remark, “For us, it is a kind of spiritual death to now be branded as Jews and exposed to general contempt.” Although Hitler turned down the petition in 1936, he did allow Hess’s pension to be transferred to Italy in 1937, albeit at a reduced amount. Furthermore, he later released Hess from the obligation to bear the name “Israel” that identified him as a Jew, as had been prescribed since January of 1939. Thanks to private contacts which the Heertz family maintained to the German Consul General in Italy, Otto Bene, Ernst Hess was even able to obtain a new passport in March of 1939, one that was not stamped with a red “J”. This allowed him to travel – something that other Jews could no longer do by this time. In June of 1939, the South Tyrol Option Agreement concluded between Germany and Italy gave the German-speaking population of the region the choice to remain in South Tyrol or to relocate to the German Reich by December 31st, 1939. As a result, the Hess family was forced to return to Germany. The family’s attempts to leave for Switzerland failed, even though two Swiss citizens had vouched for them. A planned emigration to Brazil to join Ernst’s brother Paul also went awry.

Hess was the son of attorney Julius Hess, admitted to practice before the higher courts. His mother was Elisabeth, née Heertz, scion of a family of bankers from Wetzlar. Ernst Hess was married to Margarete Witte, a Protestant, with whom he had a daughter, Ursula. At first, the family settled in Düsseldorf, moving to Wuppertal when Hess was forced to retire as a judge as of January 1st, 1936. After being beaten up by SS thugs in front of his house in the fall of 1936, Hess moved his family to Bolzano, Italy in October of the following year. He had chosen South Tyrol, a German-speaking province annexed by Italy after World War I, because he wanted his eleven-yearold daughter to be educated in a Germanspeaking environment. As early as June 1936, Hess had sent a petition to Hitler, asking for an exception to be made for himself and his daughter, who was classified a “1st-degree half-breed” under National Socialist racial ideology. In his letter, Hess referred to his Christian upbringing and patriotic political outlook, as well as to his service in World War I. The sensitive Jewish judge, who played the violin and viola at concert level, gave voice to his pain by closing his letter with the remark, “For us, it is a kind of spiritual death to now be branded as Jews and exposed to general contempt.” Although Hitler turned down the petition in 1936, he did allow Hess’s pension to be transferred to Italy in 1937, albeit at a reduced amount. Furthermore, he later released Hess from the obligation to bear the name “Israel” that identified him as a Jew, as had been prescribed since January of 1939. Thanks to private contacts which the Heertz family maintained to the German Consul General in Italy, Otto Bene, Ernst Hess was even able to obtain a new passport in March of 1939, one that was not stamped with a red “J”. This allowed him to travel – something that other Jews could no longer do by this time. In June of 1939, the South Tyrol Option Agreement concluded between Germany and Italy gave the German-speaking population of the region the choice to remain in South Tyrol or to relocate to the German Reich by December 31st, 1939. As a result, the Hess family was forced to return to Germany. The family’s attempts to leave for Switzerland failed, even though two Swiss citizens had vouched for them. A planned emigration to Brazil to join Ernst’s brother Paul also went awry.

Trusting in the assurances of Wiedemann and Lammers that he would continue to enjoy “Hitler’s protection,” Ernst Hess moved his family to the remote Bavarian village of Unterwössen near Traunstein in mid-1940, after a brief stay with his mother and sister in Düsseldorf. He selected this particular village so that his daughter Ursula could attend the Marquartstein boarding school nearby. In late June of 1941, Ernst Hess was summoned to appear at the “Aryanization Office” in Munich. When he submitted his letter of protection issued by Lammers to the SS official on duty, Franz Richard Mugler, the document was taken from him. Hess was told that the protection order had been revoked in May of 1941, and that he was now “a Jew like any other.” The Hess family never saw the original copy of the letter again. The petitions that Margarete Hess filed in Berlin with Hans Lammers and Otto Bene were unsuccessful. The contacts the family had to Fritz Wiedemann were no longer enough – the adjutant had fallen out of favor with Hitler in 1939 and had been relegated to the post of Consul General in San Francisco.

Trusting in the assurances of Wiedemann and Lammers that he would continue to enjoy “Hitler’s protection,” Ernst Hess moved his family to the remote Bavarian village of Unterwössen near Traunstein in mid-1940, after a brief stay with his mother and sister in Düsseldorf. He selected this particular village so that his daughter Ursula could attend the Marquartstein boarding school nearby. In late June of 1941, Ernst Hess was summoned to appear at the “Aryanization Office” in Munich. When he submitted his letter of protection issued by Lammers to the SS official on duty, Franz Richard Mugler, the document was taken from him. Hess was told that the protection order had been revoked in May of 1941, and that he was now “a Jew like any other.” The Hess family never saw the original copy of the letter again. The petitions that Margarete Hess filed in Berlin with Hans Lammers and Otto Bene were unsuccessful. The contacts the family had to Fritz Wiedemann were no longer enough – the adjutant had fallen out of favor with Hitler in 1939 and had been relegated to the post of Consul General in San Francisco.

Berta Hess was murdered

Ernst Hess was deported to Milbertshofen, a concentration camp for Jews near Munich, where he was forced to toil under the watch of SS officers. Later, he was assigned to the barracks-construction firm L. Ehrengut as a common laborer, and housed by the Gestapo in a “Jew House” owned by the jeweler Karl Silberthau in Nibelungenstrasse 12. The only thing still protecting Ernst Hess from deportation was his “privileged miscegenated marriage” to Margarete Hess. After the Ehrengut compound was destroyed by Allied bombs in 1943, Hess was assigned to plumber Georg Grau, serving as a forced laborer until April 20th, 1945. During this time, Margarete Hess lived in Unterwössen in a damp washhouse with her parents, while daughter Ursula was forced to work in the factory of the Alois Zettler electrical firm in Munich. When the nightmare of the Third Reich had finally ended, Ernst Hess decided against returning to the judiciary, despite having been nominated as president of a Regional Court in what was later to become the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. After all he had gone through, he said, he could scarcely be a “proper supervisor” to all those former colleagues who now cozied up to him, expecting to be given a document whitewashing their conduct during Nazi rule. Although he was aware that this meant he would end up penniless, he declined the appointment to the Düsseldorf court.

Through personal contacts, he was ultimately offered a job with the Reichsbahn (later Deutsche Bundesbahn) national railway, which was looking for executives with a clean record. Hess began his new career in 1946. From 1949 until 1955, he served as President of the German Federal Railways Authority in Frankfurt/ Main.

Through personal contacts, he was ultimately offered a job with the Reichsbahn (later Deutsche Bundesbahn) national railway, which was looking for executives with a clean record. Hess began his new career in 1946. From 1949 until 1955, he served as President of the German Federal Railways Authority in Frankfurt/ Main.

After receiving the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany, he was awarded a plaque of honor from the City of Frankfurt in 1970. He died there on September 14th, 1983. The privileges granted to Ernst Hess did not ease his family’s plight in Düsseldorf. His mother Elisabeth (born 1866) and his sister Berta (born 1888) talked themselves into believing that the “protection” accorded to Ernst also extended to them. When their status was reviewed in 1942, it was established that they did not carry a Jewish identity card, did not wear the yellow star, and had not duly marked their apartment in Brend’amourstrasse as a Jewish residence.

Moreover, Berta Hess had told people in Düsseldorf- Oberkassel that she “enjoyed the special protection of the National Socialist Party.” Adolf Eichmann of the Reich Main Security Office in Berlin went out of his way to categorically deny this, personally signing the deportation order for both women. On July 21st, 1942, Elisabeth and Berta Hess were transported to Theresienstadt. Berta Hess was murdered shortly thereafter in Auschwitz. Her mother Elisabeth was able to escape the Nazi death machine when she took the one and only train leaving Theresienstadt for Switzerland on February 5th, 1945. She never returned to Germany and joined her son Paul in Brazil.