“Dear John, I hope you will come home at Christmas,” a young boy writes to his elder brother who left England for Germany almost 200 years ago. Today, his great-great grandson, Christian Lawrence, a German manager, tells the story of his Anglo-German family and explains why we should make every effort to keep British political values, British economic principles and British pragmatism in Europe…

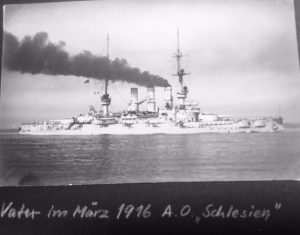

John Lawrence’s grandson John served in the Imperial German Navy during WWI

(c) Christian Lawrence Privat

Here’s an anecdote from the height of the Empire that offers a revealing view of the British soul. A French diplomat, trying hard to be polite, told Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, “If I were not French, I should want to be an Englishman.” Palmerston replied, serenely, “If I were not an Englishman, I should wish to be an Englishman.” To be sure, this kind of self-assurance could be found not only in the United Kingdom especially in the 19th century, the age of the nation state. Probably in no other country has this sense remained as unshakable as in the UK, and by no means just among societal elites. One small but revealing sign of this is the box office success of the evacuation drama Dunkirk. The mystique of the British Isles as a sanctuary, a safe haven from the threat of persecution by alien powers holds its sway to this day. And haven’t we Germans always envied the Brits for this very reason? Is not this ever-redoubtable Britishness that we have always acknowledged as the most elegant example of the national self-esteem so essential to every society? While in Great Britain a blend of confidence, irony, and common sense has found pragmatic solutions for mending the fabric of society, the in-group/out-group tension that sociologists have identified in Germany can apparently be resolved only through the periodically recurring, awkward debate over what “German culture” really is and should be. This takes place mostly without any new insights, and results instead in a measurable rise in popular alienation from establishment politics.

Cross-cultural influences

The close-run Brexit referendum result of June 26, 2016 – even if it does not result in a “hard Brexit” – deprives Europe of this specifically British brand of political culture. In a Europe currently facing an array of uncertainties at home and abroad, this is a luxury we can hardly afford. I feel this looming loss personally not only because my family’s origins are in Britain but also because it was marked by the British-German rivalry and two world wars.

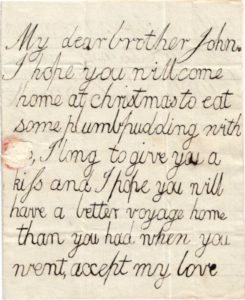

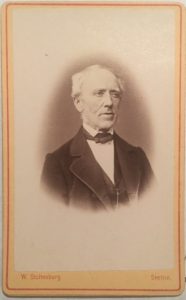

My great-great grandfather John Lawrence was born in the London borough of Southwark, the sixth of eleven children. His father painted houses for a living and the family lived a mostly hand-to-mouth existence. A family friend, a Jewish merchant named Moses Nathanson, organized an apprenticeship with his son Isaac, an importer of British goods based in the town of Güstrow in Mecklenburg. Seventeen-year-old John moved there in 1830. In later years he set up his own business as a watchmaker in Stettin, which was then the capital of the Prussian province of Pomerania and today is called Szczecin, the capital of the Polish administrative district of West Pomerania. Surviving letters confirm that he kept contact with the family he left behind in London. Then, the paths diverged. The emigrant’s grandson, likewise named John, joined the Imperial German Navy in 1898. He spent the First World War as an officer on various big warships. His son – my father Peter (born 1920) – joined the German Kriegsmarine in 1939 and, as a U-boat commander in World War II, was intensively engaged in the struggle against the chief enemy, the Royal Navy. In Norway when Germany surrendered, he spent two years in English and Scottish POW camps before returning to Germany and, in 1956, became one of first officers in the newly founded West German Bundesmarine. In the 1990s, the British-German family circle began to close again. I was transferred to London by a German company; my son John was born in the city and holds German and British dual citizenship. There is no more contact, however, to the surely abundant and far-flung family in the UK.

Young Campbell Lawrence misses his brother (1832)

(c) Christian Lawrence Privat

This single example among millions reveals the kinds of subtle cross-cultural influences and undercurrents that so many people in Europe carry within them. From our joint history we can readily conclude that any weakening of Europe’s powers of keeping peace must be avoided. In his day, Helmut Kohl was laughed at for his remark that the unification of Europe was a choice between war and peace. Today, we would not be laughing. None of this, of course, lessens the referendum choice for or against the EU – such a referendum was already held once before, in 1975. What matters is the style and substance of the debate. It is grossly negligent to reduce Europe to an assemblage of grievances, the pre-Brexit public discussion in Britain often did. The oldest trivialities were trotted out – about EU regulations on how bent cucumbers could legally be, or the idea of classifying Scotch whisky as a “flammable liquid” and therefore dangerous chemical, requiring drastic safety precautions, to name but a couple of examples.

Dismissive media

This is where the role of the media – which is and remains a chief influence on the forming of public opinion – comes in. By a lopsided majority, the British media supported the agenda of the pro-Brexit camp. For decades, the terms “Brussels” and “Europe” were deployed as defamatory shorthand for bureaucracy and the nanny super-state that would like nothing better than extinguish the British people’s cultural identity. In the echo chambers of social media, these negative impulses were massively amplified; a dynamic also recognizable among populist movements elsewhere. Notwithstanding the axiomatic avowal of freedom of speech and the press, previously in Great Britain there was also always a tacit consensus regarding the role of the media. It was always accepted that the media are there to give people orientation, show the opportunities and risks bound up with change and, when the time came, to enter into a skeptical exchange with those offering solutions. Many media outlets in the UK no longer provide this orientation. “Europe” was denigrated and dismissed. The result was a public unease that was left unaddressed by any constructive summation of what the people want. Brexit has come because in the UK – as well as in parts of continental Europe – there was no vision for Europe that people could make their own. People do, however, want to do their part in working toward a better world, simply put. After the referendum, when the European idea seemed headed for the abyss, that message was heard once again, first in France. The result: Emmanuel Macron.

John Lawrence had left England

(c) Christian Lawrence Privat

Today, the UK seems left behind and saddled with years of ultimately unproductive damage limitation. The Brexiteers have long stopped citing the supposed economic and political blessings they once touted so highly. Today, the job is simply to deliver “the people’s decision” for Brexit. Yet the interests of Europe – very much including the UK – lie in finding responses to the four truly great challenges of our age, namely globalization, climate change, terrorism and migration. With the triggering of Article 50 of the EU Treaties last spring, all visible efforts on the part of the British government regarding these challenges have ceased. The country’s entire political capacity is currently occupied by merely gaining an overview of the countless follow-on problems that Brexit will bring, without managing to convey even a halfway cogent blueprint for the future. Brussels is impatiently waiting for the British negotiating positions that do not yet exist – because the British themselves cannot reconcile the mutually exclusive demands of restricting the movement of labor and keeping maximal access to the European market.

A growing chorus of voices is demanding a second referendum in 2019 once the framework conditions for Brexit have taken shape. What shape that will be is something no one knows today. Every effort should be made, however, to keep British political values, British economic principles and British pragmatism in Europe. Europe’s past, future and, very immediately, present predicament all call on us to do so.

In history as in life, nothing is over until it’s over. Perhaps there can still be an exit from a Brexit that would harm all of us. We and our governments should try to find that exit. ■

Christian Lawrence is a partner at the strategic communications consulting firm Brunswick Group. The article expresses the author’s own personal opinions