James Simon bequeathed the city its most famous treasure, the bust of Nefertiti. Even today the spell of the Egyptian queen is unbroken. But the man who transformed the provincial collections of Berlin into galleries of international standing was also a passionate philanthropist.

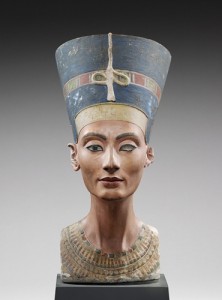

For seven years she was his and his alone. Admittedly, there was the slight problem of an age gap. She was a mere 3,000 years his senior. But her beauty had not withered, her serenity had not faded. It is hard to believe she once jostled for space on a mantelpiece in his Berlin villa crammed with exquisite artifacts. But she was his one and only. The Queen from the Nile, also known as “The Beautiful One has Come” – or Nefertiti.

A penchant for the arts, antiquities and archeology

But notions of “just for me” never sat easily with James Simon. He lived tzedakah, the Jewish law of righteousness and mercy. Aware of his privileged station in life, Simon wanted to give and to share. Born in Berlin in 1851 as the son of a wealthy cotton merchant, young James had a penchant for the arts, antiquities and archeology.

His father however had other plans for the boy. Isaac Simon considered digging about in the dirt for ancient bits and bobs an unsuitable way to earn a crust. James was to join the family business. Which he did, helping to bring the already profitable business hitherto unknown levels success. He married the beautiful Agnes Reichenheim also from a well-to-do Jewish family. By all accounts a happy match.

The best and worst of times

The golden couple was living through a purple patch in German history. In 1871, Germany had become a unified nation, the Second Reich, and it was brimming with power and self-confidence. A huge industrialization process saw Berlin quickly becoming the leading industrial center in the country.

Many turned a blind eye to the plight of the working classes. They slogged for long hours, often living in dark and damp accommodation. Hygienic conditions were catastrophic.

James Simon did not look the other way. He was among the first to establish mobile, and then permanent, bathhouses. Simon was especially compassionate toward the weakest links in the ruthless chains of the industrial age – children. He sponsored projects to ensure that poor youngsters got to enjoy holidays at the seaside and he provided for education among the poorest in the city.

He also built a large house amidst beautiful gardens in the wealthy Zehlendorf quarter of Berlin for battered and abused children. In ‘Haus Kinderschutz’ mistreated youths found a home, receiving schooling and vocational training. The highest level of tzedakah: to enable the recipient to become self-reliant.

Simon founded “Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden”

But it was not just Berliners who were on the receiving end of Simon’s charitable works. At the turn of the 20th century, hard times befell the Jews of Eastern Europe with intermittent pogroms spreading panic and fear.

Together with the politician Paul Nathan, Simon founded the ‘Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden’, a charity helping the persecuted to emigrate to the United States and to Palestine.

Simon had another passion: art. Antique coins, Medieval and Renaissance sculptures and paintings of the highest quality, he collected it all. In 1885, he made his first donation to Berlin Gemäldegalerie. For the next four decades he would give away his finest treasures. Thus transforming the hitherto provincial Berlin collections into galleries of international standing.

From business to patronage

Simon was also co-founder of ‘Deutsche Orient Gesellschaft’. At the time there was a craze in Germany for anything considered exotic, particularly if it came from the Levant, the biblical lands. Simon started funding excavations at Babylon, Jericho and other ancient cities. The finest finds were brought back to Germany and subsequently donated to the museums of Berlin. The most spectacular gift is the gigantic Ishtar Gate from Babylon which still enthralls visitors to the capital’s Museum Island.

A spectacular discovery

In 1912, Simon financed digs at the ancient Egyptian capital of Amarna. The expedition was headed by Germany’s top archaeologist, Ludwig Borchardt. On December 6, 1912, Borchardt made a spectacular discovery – the bust of Nefertiti, chief consort of Pharaoh Akhetaton. Overwhelmed, Borchardt jotted down, “It is indescribable. You have to see it with your own eyes.”

As soon as Nefertiti arrived back in Berlin in 1913, James Simon got to see the ‘Beautiful One’ with his own eyes. In 1920 he donated the bust, together with many other finds from the Amarna dig to a Berlin Museum.

Soon after, Simon and his firm fell on hard times. He had to use the best part of his private assets to ensure his firm’s pension funds were safe. James Simon died in 1932.

Back into the limelight

For decades, Berliners neither knew nor cared as to how they came to posses one of the world’s most exquisite pieces of antiquity in their city. For a man of James’ standing, surprisingly few photographs have survived. What he had not already donated to museums, he had to sell, including a Rembrandt and a Vermeer. For a long time, all that reminded the city of its generous patron was a plaque on the house where Simon spent his twilight years.

Recently however, Berlin’s collective memory has opened itself back up to Simon, albeit gradually. Simon, once among the leading figures of the city, is finally returning to his home town. A foundation in Simon’s name was created, a public swimming pool was named after him, a small park now bears his name. Perhaps more aptly, a new building on Berlin’s Museum Island will bear the name ‘James Simon Galerie’ upon completion.

A recent TV-documentary has traced his fascinating life, James Simon, the man who gave Nefertiti away.

The unbroken spell

The Egyptian queen’s spell is unbroken to this very day. In 2009, Nefertiti moved into her new home. She is the chief attraction at the Neues Museum on Berlin’s Museum Island, a World Cultural Heritage destination. More than one million people pay tribute to Nefertiti each year.

‘The Beautiful One’ has the somber and festive Nordkuppel hall all to herself. Well, almost. For across the room there is small bust – a likeness of James Simon in bronze. So when the crowds recede and darkness engulfs the museum, just the two of them remain. The ancient, forever young and beautiful monarch and the generous philanthropist and lover of the arts. It is just as it was in the beginning, one hundred years ago in Berlin, when they first set eyes on each other.

Nefertiti and other finds from the Amarna digs are currently displayed as part of the exhibit In the Light of Amarna. 100 years of the Nefertiti discovery.

Hannah Thiel is a Frankfurt based journalist